Everyone on the athlete’s recovery-to-play team needs to be able to talk each other’s language. They don’t have to be an expert in all areas, but they should make friends with someone who is an expert. No one person, no matter what letters they have after their name, can do it all.

I personally became a much better clinician when I started hanging out with strength coaches because the more I understood what the athletes had to get back from a strength, conditioning and performance standpoint, the better I was able to prepare the athlete to return to play.

In the past, I believe there have been gaps in the rehab-to-performance process because everyone worked in silos. Typically when an athlete gets injured on the field, the athletic trainer is the one who assesses them and immediately tries to figure out what referrals they need, where they’re going to go and what surgeon they need to see.

Once they’re done with the surgery, they go to a physical therapist for rehabilitation. At the same time, they may be working with their strength coach who’s likely in another building. So whether it’s from a philosophical or from an actual location difference, people have unfortunately worked in silos.

Today’s digital technology has greatly improved the ability to communicate between providers and to get them all on the same page. But we’re dealing with athletes and they’re physical; their providers have to have their hands on them. So a shift to getting all providers under one roof is the ideal way to eliminate the silos and the gaps. This, however, may not be possible. When physical proximity can’t be altered, it is imperative to assemble a team of people who have similar philosophies.

And how do you put together such a team? My philosophy is to be inclusive; there’s room for everybody. There’s so much that needs to get done to return an injured athlete to their sport. When you think about all the things that the athlete needs to deal with, it’s never just about a knee injury, for example. I’ve got to get their range of motion back and their general strength back and work on their hips and their legs. But during that process, if they’re not working with the strength and conditioning coach to maintain the strength and power in their other leg, upper body andcore, then we’re losing time. An athlete can’t afford to focus only on his knee for six weeks.

We may have to bring in a nutritionist because the metabolic demands of someone who’s injured is totally different from someone who’s not. We need to make sure that they’re optimizing their body composition during the entire process and they don’t lose a ton of muscle mass. If they’re not sleeping because they’re in pain, we may want to bring in a sleep specialist. If they’re in a lot of pain, we don’t need to go down the pharmaceutical route and instead might utilize acupuncture or other pain relieving modalities to help with pain control.

Athletic trainers can work in very different situations. There are athletic trainers who work in high schools and never have the opportunity to rehab their own athletes because they’re dealing with 300 or 400 student athletes. So they have to be able to integrate and work with local physical therapists to manage that athlete as a whole. Just because an AT is not physically doing the rehab, they’re probably helping the student manage their school work and helping them manage what’s going on with their coaches and team mates.

Often the athletic trainer is the quarterback of the whole thing; they’re the ones saying “You need to go see a doctor,” and “Here’s a doctor that’s local,” or “You want to see a specialist? This is where the best shoulder surgeon is.” Maybe the athletic trainer is the one researching and they can advise the athlete based on their own lit review to say, “You know what, the risks are low, the rewards could be high, so this intervention may be worth considering,” or “This really has a lot of risk, I would caution you against it.”

Because the athletic trainer plays a pivotal role in general management and coordination of what’s going on with the injured athlete, they need good communication skills. They’ll likely be dealing with people with different personalities, desires and /or egos and that can be a lot to manage. They may often be the one that extends that olive branch and says “How can I help?”

Athletic trainers can have such a wide variety of expertise that sometimes other healthcare professionals don’t know specifically what they do. Being able to educate other professionals on their role and process and saying, “I’m an athletic trainer and here are my areas of comfort and expertise and how I think maybe I can help you.”

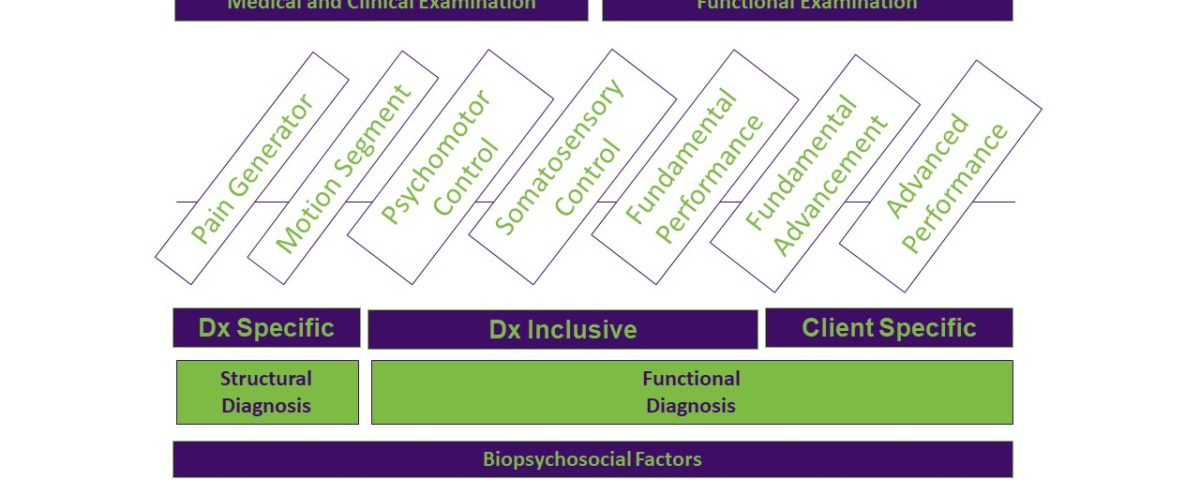

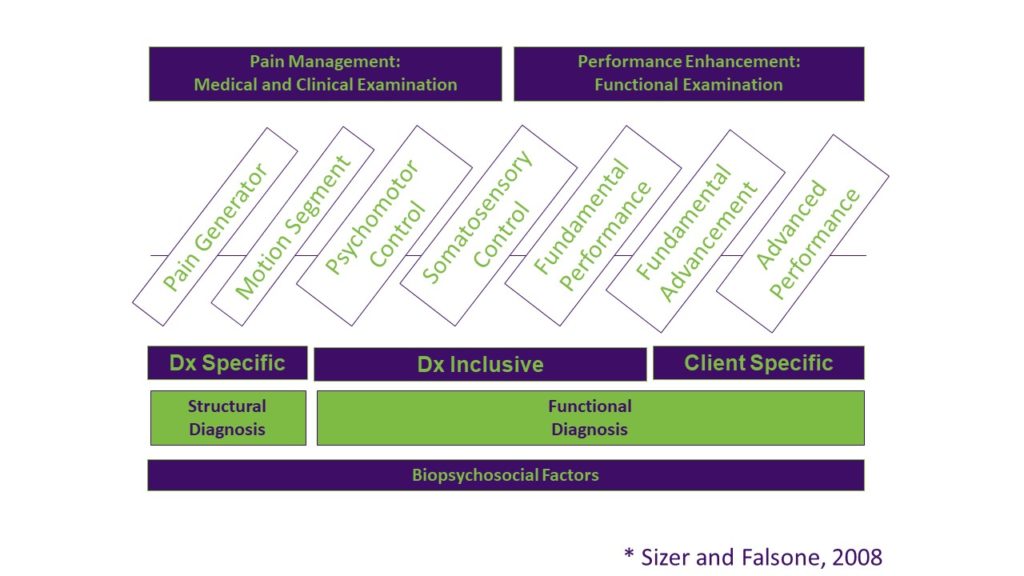

As I point out in my book, Bridging the Gap From Rehab to Performance, understanding the roles of everyone involved in getting the athlete from rehab to performance is imperative to best meet the needs of the athlete. The book provides insight into how each specialty fits into the rehabilitation and performance continuum and hopefully provides a deeper understanding of the significance of other complementary roles.

As the reader goes through the different sections of the book, they’ll be asked to think about the information being presented and decide what tools they have in their tool box that would fit in that section. Once they decide what tools to use to address the main factors of each section, they may see holes in their education or knowledge that need to be filled. At the very least, this thinking will help the reader decide what professional relationship they need to cultivate for the betterment of their athlete.

My hope is that all readers will be able to recognize where their strengths fit in an athlete-centered bridging-the-gap model and that they are humble enough to see those areas needing improvement in a new light. This will better inform the gaps in their care strategy and guide them in expanding their network to include professionals who are experts in the skills they do not currently have. What we do is an art, based on science, and the art of what we do is what makes us unique clinicians.